“– We want to change people’s lives through sound and music, and have sound and music really adapt to their everyday lives’– Now, that would be a great brief… and it’s short!” Yves Béhar, designer of Jambox portable speaker for Jawbone, 2010.

Béhar’s example of a great brief, apart from being, well, brief, is an open statement. Not prescriptive, not restrictive, an excellent starting point which allows the designer to be creative, inventive and pioneering.

At the core of design is the design brief, and the DT curriculum naturally reflects this too. As Béhar notes, the way in which a brief is written has a profound influence on the type of responses it will inspire, whether in the real world or in the DT classroom. I’ll demonstrate this using two projects that regularly feature in schools: Chairs and Lights.

Let’s take a brief along the lines of:

‘Design a chair… (in the style of… / to be used in…/ to be used by…)…’

And instead try something like:

‘Design a way to help us sit comfortably…(when out and about / when there is no chair available / that can be used on the go)…’

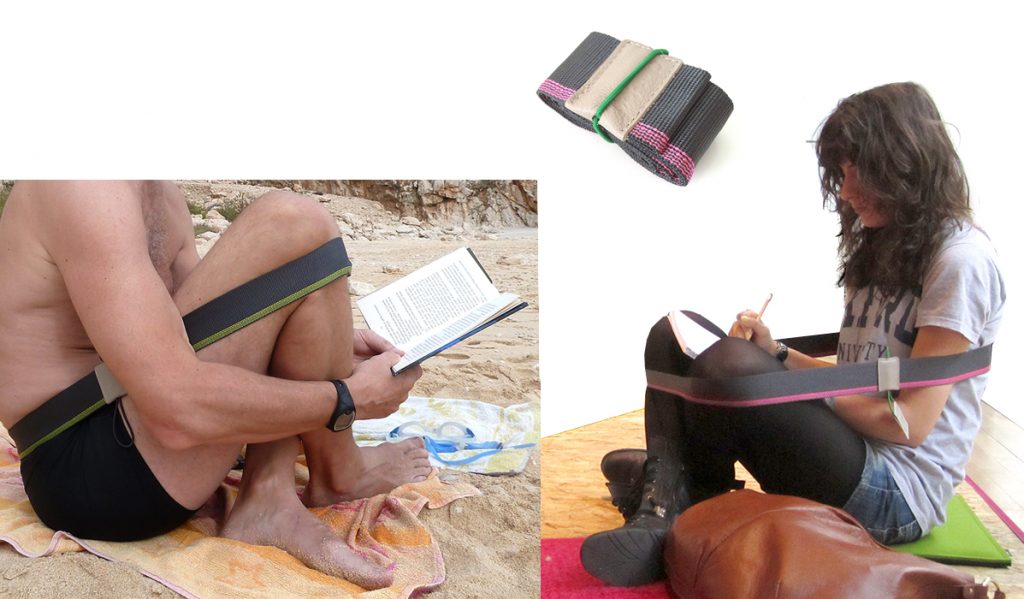

Perhaps we will end up with a response such as this?

Chairless, designed by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena and manufactured by Vitra, is a textile strap which is ‘worn’ around the back and knees, supporting and relieving tension when in a sitting position. The strap can be rolled up and carried around with ease.

In addition to taking pressure off the back and thigh muscles, Chairless also frees the sitter’s arms so they can be used instead for eating, reading or texting.

Though not strictly a chair, it functions as an aid to sitting when no chair is available – which makes ‘Sitting’ both a Chair and Chairless’s prime function.

On to lights. Instead of:

‘Design a light… (in the style of… / to be used in…/ to be used by…)…’

Consider: ‘Design a way to illuminate a space’

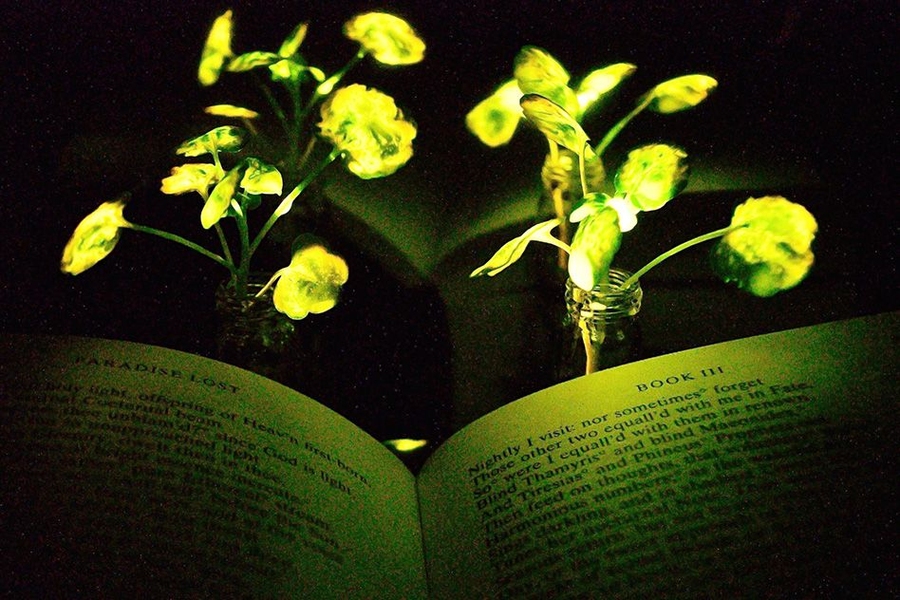

…and you might encourage solutions such as this:

The designers of Glowing Plants developed plants that emit light from their leaves by immersing them in the same enzyme that gives fireflies their glow. At this stage of the research, plants can only give off dim light for a limited time, but scientists believe with further development plants will be bright enough to illuminate a workspace.

These two cases demonstrate how, by refraining from specifying the desired outcomes in the brief (in these cases ‘a chair’ or ‘a light’) we can allow students the freedom to think both deeper and wider about the challenge.

Another way to get better at both writing and responding to briefs is to try and think backwards – from a final product to its imagined brief. Though not a way of working we would encourage, students will often do this with their own ideas anyway, writing a brief to suit an idea they’ve already come up with. So why not develop their skills and get them to learn something new along the way?

Here’s an example:

What sort of brief would bring about designing a cycling glove with a smile featured on it?

According to Loffi, the company behind the gloves, …”we were becoming increasingly aware of rising levels of aggression and conflicts between cyclists and motorists in London and so we started thinking about how this relationship could be improved.”

If this statement was a brief, it might read something like:

‘Design a product that would improve the relationship between car drivers and cyclists in the city’. Open, non prescriptive and inviting many different responses, of which smiling cycling gloves is just one, albeit a small and sweet demonstration of design that encourages behaviour change.

And finally, we must also acknowledge the many products out there, some real design classics, that may not have been created to a brief at all.

Take Philippe Starck’s notorious Juicy Salif (discussed in detail in my post Learning with objects). This lemon squeezer turned design classic was born from a doodle on a paper placemat while Starck was at a restaurant eating calamari. No mention of a specific design brief, according to Alberto Alessi’s own account. Just a greasy paper mat covered in little drawings.

Can you imagine the equivalent DT project brief? How about ‘Design a product inspired by what you ate yesterday’? ; ‘Think of a more interesting way to squeeze a lemon’? or maybe ‘Create a functioning product from one of your doodles’? Short, not too prescriptive – would Yves Béhar approve?

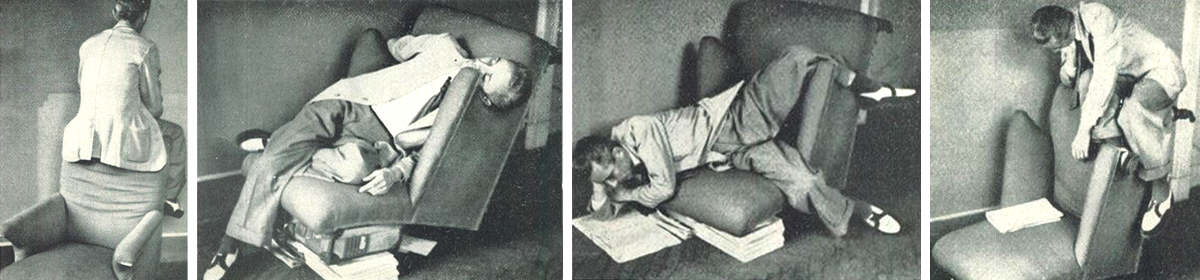

Photos: Chairless strap: flickr CC m-s-y; Chairless people: flickr CC, charclam,Anette Munthe;Header: Bruno Munari, Seeking Comfort in an Uncomfortable Chair, published in Domus 202 / October 1944

This is a great article with really good examples but it slightly muddles two things: designing and what the Design Education Unit at the RCA in the 1970s came to call ‘design educational activity’. That’s a bit of a mouthful but it draws attention to the difference in purpose between using designing as a vehicle for learning (what teachers do) and designing to create artefacts and systems (what designers do). Design education came into British schools from the late 1960s recognising the potential of practicing the latter to achieve the former. And that’s OK because that’s the core of what design in education is about, which means it can have vocational relevance but most importantly . . it involves kids in complex problems and learning how to work through them, from coming to understand the ‘problem’ to reaching a practical resolution of it. A special experience to have in school. And the brief? In education that importantly provides a context within which to work that gives a reality to the constraints that must apply. Which is why it makes ‘real’ designing more challenging and demanding than the ‘design a fantasy machine’ type of task that is quite common.

Really insightful point, David. My work with young people uses the ‘design as a vehicle for learning’ approach, in the belief that skills developed through ‘design education activities’ are relevant, and often essential, to almost so many areas of study and life. Within the specifics of briefs, I agree that the learning opportunities from the ‘design a fantasy machine’ type of brief is limited. However, being aware that design briefs that are less prescriptive challenge our students to think differently, is important. Even briefs for ‘classic’ DT projects such as desk tidies and automata toys can be phrased in a way that would push thinking beyond one defined, expected outcome.