“Empathy is the capacity to step into other people’s shoes, to understand their lives, and start to solve problems from their perspectives. Human-centered design is premised on empathy, on the idea that the people you’re designing for are your roadmap to innovative solutions…” Emi Kolawole, Editor-in-Residence, Stanford University d.school

We ask students to consider who they are designing for at every step of the design process. Exam boards specify students should …”develop realistic design proposals as a result of the exploration of design opportunities and users’ needs, wants and values.” (from The AQA D&T GCSE scheme of assessment).

Is it fair to say though that teenagers are not renowned for their empathetic tendencies? They may not have had enough life experiences themselves to be able to see beyond their own bubble, and this is perfectly natural. By asking them to identify, explore and understand ‘different users’ needs wants and values’, should we be surprised that many will resort to circulating a questionnaire amongst their peers and conducting a Google search or two?

I’d like to propose two examples that emphasise the importance of really understanding the user. They demonstrate how placing the user’s needs at the centre of the design process can allow for truly innovative solutions, with possible impact far beyond the initial problems they set out to solve.

CHILDREN ARE NOT MINI ADULTS: It was not till the late 1990s that children’s toothbrush manufacturers really started paying attention to their target users. When Oral-B asked design firm IDEO to design a new line of kids’ toothbrushes, IDEO suggested they begin by watching children brushing their teeth. Seems pretty obvious, right? The fact is that till this moment children’s toothbrushes were designed with the assumption that the only difference between these and adults ones should be their size – kids’ hands are smaller, so kids’ toothbrushes should be smaller, with a thinner handle.

Observing a 5 year old boy brushing his teeth, the IDEO team immediately noticed that the important difference lay not in the size of the boy’s hands, but in the way he was holding his toothbrush: gripped in a fist rather than held between his fingers.

Observing a 5 year old boy brushing his teeth, the IDEO team immediately noticed that the important difference lay not in the size of the boy’s hands, but in the way he was holding his toothbrush: gripped in a fist rather than held between his fingers.

From here, the path to a new design solution was clear – and a new squishy grip toothbrush was born. All children’s toothbrushes were quick to follow.

From here, the path to a new design solution was clear – and a new squishy grip toothbrush was born. All children’s toothbrushes were quick to follow.

ONE SOLUTION CAN HAVE A BIG IMPACT: Women and children carrying heavy containers of water on their heads is an image many are familiar with. What we might not consider though is the time the task takes up, the health implications this heavy load can have on the carrier’s spines, the risk of spillage and the physical challenge of negotiating rough terrains.

Designed to offer a better way of carrying larger quantities of water from remote sources to rural villages, the hippo roller combines a wheelbarrow with a water container that can be easily manoeuvred over long distances. By increasing the volume of water carried in one journey, the hippo frees up time which can be used for education or work. It improves the health of those tasked with carrying the water, and even has an impact on their sense of dignity: one young women described the joy of braiding her hair nicely when going to collect water with the hippo, as she no longer had to carry a heavy load on her head.

IDEO’s method of design emphasises two crucial stages: observing and empathising. In simple words: watch how the user uses, and try and feel what they feel. Easier said than done, especially if we go back to our target audience – school age young people.

In my practise, specifically working on adapting and delivering the Fixperts method in schools, I found that sometimes ‘tricking’ students in to feeling empathy (nothing sinister, I promise!) is an effective way of triggering a deeper investment in finding a good solution. These activities came about as a way of addressing the difficulty in matching students with relevant users they could interview, observe and test their prototypes on. They offer an easy-to-implement alternative, which as well as being fun, makes a strong case for the importance of empathy in design.

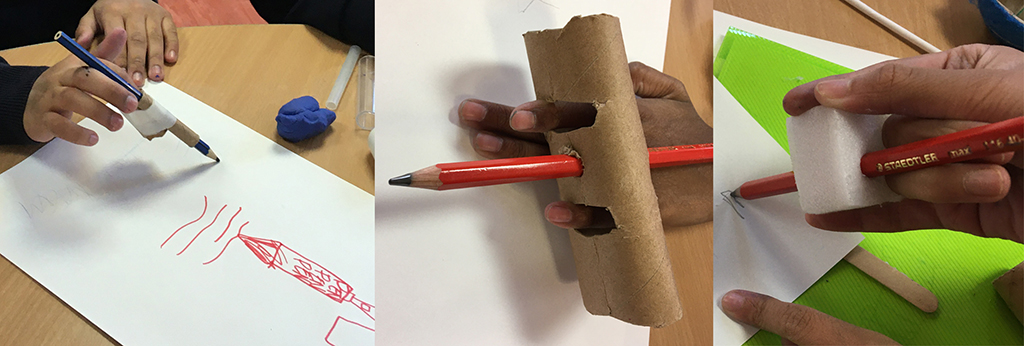

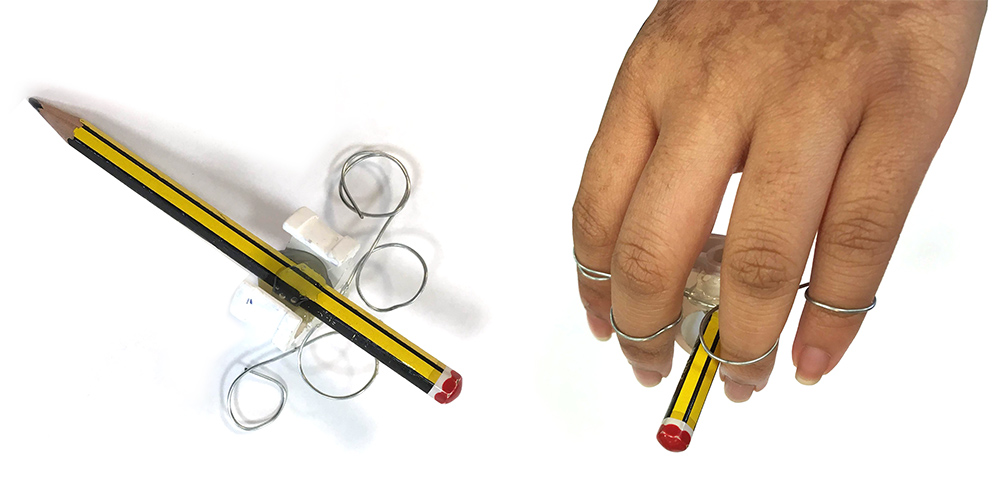

I came up with a series of simple simulations that allow students to experience a problem on their own person: they physically feel the challenge, explore different ideas for solutions, and test solutions on themselves with immediate feedback on whether they work or not.

If you’d like to try this out, here’s an idea: Ask students to design or modify a pencil for a user with diminished finger dexterity. They can tape lolly sticks to their fingers so they can’t bend, tape a few fingers together, or just hold down their two middle fingers so they’re only using index finger and pinky.

Whatever solutions they come up with, they will, perhaps without even noticing, have designed for someone with an experience different to theirs. And that, my friends, is empathy.